(Reprinted from the November 2023 issue of New York City Jazz Record)

A year ago October, Leopoldo “Pucho” Escalante, a heralded trombonist from the golden age of Cuban jazz, passed away in New York City, two months shy of his 102nd birthday. Though largely overlooked today, Pucho and his older brother Luis made a lasting imprint on Latin jazz, not just for their ground-breaking musicianship, but for their mentorship of the next generation of influential players.

It was Luis who first tapped a teenaged Arturo Sandoval, in 1967, to play trumpet in the Orquesta Cubana de Musica Moderna (Cuban Orchestra of Modern Music), the ground-breaking Cuban big band ensemble that Luis formed, along with conductors Armando Romeu and Rafael Somavilla. Pucho was the group’s dedicated trombonist and one of its principal arrangers.

“Actually, Luis did something very special for me when I was 16 years old,” reported trumpeter Arturo Sandoval in a phone interview with New York City Jazz Record. “He was the first trumpet in the best orchestra that ever existed in the history of Cuba. And when he left, he put me in a spot. Everybody was against that. I was such a risk because I [had] just come out of school and didn't have any experience at all. But he had a lot of confidence in me—he had the vision that he saw something.”

Sandoval’s brief but formative tutelage with the Escalante brothers would end in 1971, the year that Luis died, at age 56. Soon thereafter, Sandoval and fellow OCMM alums pianist Chucho Valdez and clarinetist Paquito D’Rivera founded Ikarere—the historic ensemble that introduced Cuban-based jazz fusion to the world.

One can trace the musical lineage of Irakere directly back to the Escalante brothers and their ready embrace of the jazz innovations that were pouring into Cuba from the US in the first half of the 20th century. Growing up near Guantanamo, the brothers started their music education early, with Luis teaching himself the trumpet and cornet and Pucho studying the trombone more formally. At the time, these brass instruments were crucial to the sound of Cuba’s popular dance bands, and before the brothers had barely reached adulthood, they were gigging at Havana’s finest clubs and cabarets with some of the country’s most prominent bandleaders.

Luis, too, aspired to conductorship and soon parlayed his growing reputation as a premier big band trumpeter into a leader role: In 1940 he and Romeu formed the Bellamar Orchestra, the house band for the upscale cabaret Sans Souci, with Pucho in the trombone chair.

While much of their careers overlapped, Luis and Pucho didn’t always work side by side. As Luis continued to work as a sideman or leader within Cuba, Pucho began to accept opportunities abroad. In the 1940s he moved to Panama to play with Armando Boza’s famed big band for several years, later relocating to Venezuela, where he worked with Luis Alfonzo Larraín, the beloved Venezuelan composer, and Billo Frómeta, the founder of the Billo's Caracas Boys ensemble. In these rich musical environments, Pucho thrived.

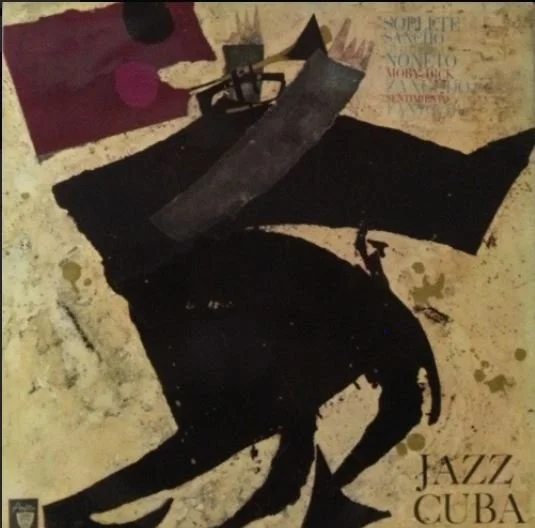

In 1959—the year of the Cuban Revolution—Pucho decided to move back to Cuba, again working prolifically as a sideman and composer. But, like his brother, Pucho had the skills to lead, and in 1963 he formed Noneto Cubano de Jazz, a vehicle that made full use of his innovative musicianship. Here, the brothers’ usual roles were reversed, with the younger Escalante on the bandstand and the elder following. This nonet, as much as any other ensemble, would lay the creative groundwork for the formation of OCMM in 1967.

(An aside: Following the success of the film Buena Vista Social Club in 1999, record label EGREM released the album Sentimiento, identifying pianist Rubén González—one of the film’s featured artists—as the album’s principal performer. In fact, this album was a re-release of the 1964 LP Pucho Escalante y su Grupo de Jazz Cubano, with Pucho cited as the album’s producer, musical director, primary composer and trombonist.)

After Luis’ death, Pucho returned to Venezuela, where he found ample work on television, recordings and jazz stages. By the mid-1980s, he had made his way to New York—still performing and recording, but less visibly. His most prominent appearance in the US from that time was, arguably, the 2001 recording Generoso Que Bueno Toca Usted (Pimienta), which received a Grammy nomination for Best Traditional Latin Album in 2003. Most poignantly, this record would reunite Pucho with D’Rivera and Sandoval in the studio—to pay tribute to another trombonist from the golden age of Cuban jazz: Generoso Jimenez.

Thanks to Patrick Dalmace and Rosa Marquetti for their extensive research on Luis and Pucho Escalante.